INTERNMENT AND SS DUNERA

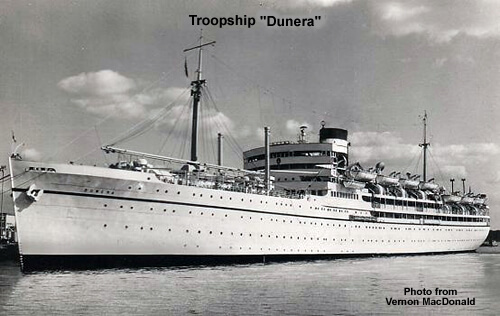

Lack of understanding of the plight of European Jews by British and Australian authorities was evidenced in the fact that some Jewish refugees were labelled as ‘enemy aliens’ and were required to report to the local police, receive a police pass if they wished to travel outside their suburb, and surrender their radios. Some ‘enemy aliens’ were interned initially at Hay, New South Wales and later at Tatura, Victoria. A notorious story was that of the passengers on board the Dunera, a ship dispatched from Britain with 2,542 men on board, mainly Jewish refugees, but also 200 Italian Fascists and 251 German prisoners of war. Built to accommodate only 1,600 passengers, the overcrowding led to insufferable conditions. The ship arrived in Sydney in September 1940 and the passengers were sent to the internment camps. In Hay the Jewish internees organized different academic and cultural activities, and even printed their own money. In 1942, they were finally reclassified as ‘friendly aliens’. Some volunteered for service in the Australian Military Forces employment companies, which engaged them in essential non-combat wartime work.

AUSTRALIAN JEWISH SOLDIERS

As had occurred in World War I, young Jewish men and women throughout Australia immediately enlisted for military service. A total of 3,870 Jewish service personnel served in Australia’s military forces in World War II. The most outstanding soldier of this period was Major-General Paul Cullen, son of Sir Samuel Cohen; he changed his name in case he was captured by the Nazis. After 1945, Cullen went on to build an outstanding record of community service, notably as president of Austcare. Other leading soldiers included Brigadier Joseph (“Jaffa Joe” ) Steigrad, a Sydney surgeon who was born in Jaffa in Ottoman-era Palestine; Dr Stanley Goulston, another medical practitioner and one of the ‘Rats of Tobruk’; and Peter Stuart Isaacson, who became an ace pilot and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal. Jews were also active on the home front. The Sydney Jewish community erected a Monash Recreation Hut in Hyde Park for all servicemen, staffed by volunteers from the National Council of Jewish Women.

AUSTRALIA JEWISH RELIEF EFFORTS

Following the announcement by Anthony Eden on 17 December 1942 of the Allies’ recognition of the massacre of Jews in Poland, the United Jewish Emergency Committee was formed in Sydney by Dr Jona M. Machover (a leading Zionist, originally an emigré of the Russian revolution who settled in London and was stranded in Australia during the war). In Melbourne, the United Jewish Overseas Relief Fund was formed under the presidency of Polish-born Leo Fink to raise funds and collect goods from Jews to assist their suffering brethren in Europe.

WHAT DID AUSTRALIA KNOW

During the war, Australian Jews became aware of the Holocaust. The Palestine Jewish community cabled the Australian government, informing it of the slaughter of Polish Jews by the Nazis and seeking ‘to open the gates of free countries to those who seek refuge from that inferno on earth’. By 1943, communal documents recorded the destruction of three to four million European Jews, and in November 1943 a resolution endorsed by all Australian Jewish communities, referring to ‘the parlous state of European Jewry’, was presented to Prime Minister John Curtin. It urged him to support Jewish immigration to both Australia and Palestine, and to participate in ‘any international scheme for the provision of relief to the survivors of Nazi atrocities’. Even so, most people were not aware of the full extent of the Holocaust or the exact details of the extermination program until after the war, and the Australian government made no positive response to these appeals.