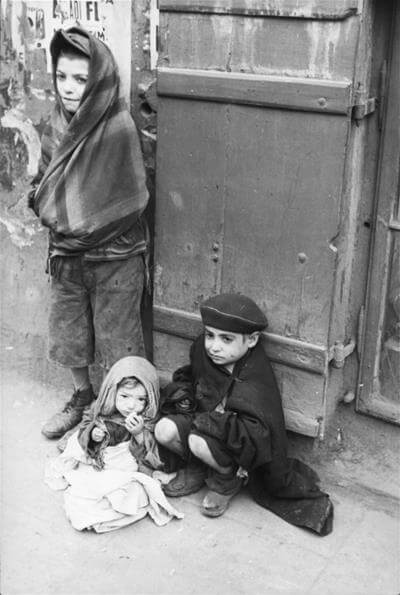

Bundesarchiv, Bild 1011-134-0778-38

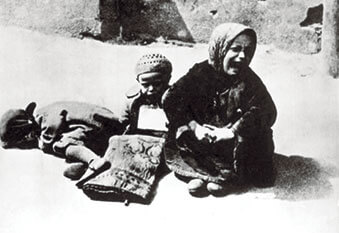

Photo: Albert Cusian Federal Archives, Germany

The term ‘ghetto’ has its origin in Venice in the 16th century. The initial purpose was to physically separate Jewish and Christian populations. Ghettos were also established in Frankfurt, Rome, Prague and other key cities in the 16th and 17th centuries.

During World War II the Nazi-instituted ghettos were places in which Jews were held as prisoners under duress, usually in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions and with severe shortages of food, water and medicines. Any signs of protest or resistance were ruthlessly crushed by the Nazis. Jews were sealed off from the rest of the population by wooden fences, barbed wire and in the case of the Warsaw Ghetto, brick walls. Over 1,000 ghettos were established by the Germans in German-occupied Poland and in the Soviet Union.

The Germans regarded the establishment of ghettos as temporary measures, in order to allow the higher echelon of the Nazi leadership in Berlin to decide upon a course of action by which to fulfil their objective of eliminating the Jewish population from Europe. Consequently, they served as transit stations on the road to extermination. The duration of ghettoisation varied considerably from a few months to several years, with the implementation of the Final Solution, the Germans began systematically to destroy the ghettos. The Germans and their henchmen either shot ghetto inmates in mass graves, located in nearby woods, or deported them to one of six death camps – Auschwitz, Treblinka, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek and Sobibor.

The largest ghetto in Poland was the Warsaw Ghetto, where approximately 450,000 Jews were incarcerated. Other major ghettos were established in the Polish cities of Łodz, Krakow, Lublin, Bialystok, Lvov, and Theresienstadt (Terezin) — a garrison town in the north of the former Czechoslovakia and Vilna, a town in Lithuania. After the ghettos were sealed, any Jew caught outside the ghetto walls was liable to be shot. The same penalty applied to non-Jews harbouring or assisting Jews outside the ghetto.