The following text is an edited and adapted version of an article written by John Berwick and published in the International Herald Tribune on October 10, 2008.

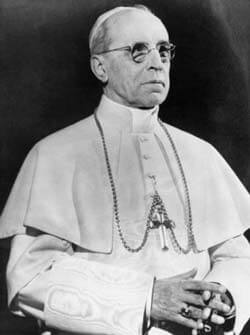

Pope Pius XII is one of the most controversial leaders of the World War II era. Yet he is controversial not because of what he did, but because of what he didn’t do.

Even though the Vatican was reliably informed about the Nazi genocide of Europe’s Jews and Jewish organisations begged him to speak out, the pope refused to publicly condemn the atrocities.

The controversy about the pope’s “silence” at first focused on his supposed motives. Many denounced Pius XII as antisemitic, as a leader who was more concerned about Vatican finances than the fate of Europe’s Jews. For many, he symbolizes a hypocritical and repressive institution willing to connive with Nazi murderers to secure its own survival.

On the other hand, some argue that the reasons for Pius XII’s refusal to back the Allied cause are well documented. As the spiritual leader of all Roman Catholics, he was convinced that his responsibility was to mediate, not participate in the conflict. Then, as the full horror of the Nazis’ crimes gradually unfolded, he was drawn into an agonizing dilemma.

As a spiritual leader whom millions looked upon for moral authority, he knew he had a responsibility to speak out. Yet he feared that a direct denunciation of the concentration camps would endanger more lives, especially ‘non-Aryan Catholics’.

The Nazis had also incarcerated thousands of Catholic priests, Poles as well as Germans, whose lives would have been endangered by a papal condemnation.

So Pius XII restricted his public utterances, making only general appeals to uphold traditional moral values. He relied on the fundamental decency of individuals to resist the Nazis as far as each person’s concrete circumstances allowed.

Since the publication of 12 volumes of documents from the Vatican archives between 1965 and 1985, questioning the motives for Pius XII’s ”silence” has died down and the debate has shifted more to speculation about what might have happened if the pope had decided to speak out more emphatically.

His critics argue that an encyclical might have saved Jewish lives. Whereas others point out that German Catholics didn’t need a papal announcement to tell them that the Nuremberg Laws contradicted Christian ethics. And even when Germany was losing the war on two fronts, the Nazis deployed much-needed resources to accomplish their terrible “Final Solution”. They viewed it as a major priority, so they were hardly likely to be deterred by a papal condemnation.

When this controversial pope has been understood in the complexity of his moral dilemma, a second more crucial question emerges: How was it possible that after centuries of Christianity in Europe, many practising Catholics actively collaborated in the Holocaust, and many more turned a blind eye to the suffering of their fellow human beings?

That was the real failure of the Church during the Holocaust. And it has not yet been adequately explained.